Purpose

The United States is in the midst of a generational, strategic shift to address two challenges: (1) a geopolitical competition with a systemic rival, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and (2) the broad implications of emerging technologies on the national security, economic prosperity, and social cohesion of nations around the world. The United States government’s pivot toward both sets of challenges is underway.1

“…the United States government will need to adjust its mission and tradecraft to advance American interests in a GenAI world.“

While the PRC poses a more “traditional”2 geopolitical challenge to the United States, the technology competition will be a paradigm-shifting issue that will require the United States government to significantly alter how it advances American interests around the world. This is reflected in the ongoing global discourse on the game-changing ramifications of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) on not just national security, but also work, education, social interaction, and other aspects of our lives.3

The current U.S. lead in GenAI, with U.S. companies demonstrating the continued “innovation power”4 of the United States, creates a unique moment for U.S. global leadership to chart the way forward on how this technology can be used for good, and to work with allies, partners, and even rivals to put in place appropriate governance guardrails to prevent or mitigate negative consequences. To achieve this, the United States government will need to adjust its mission and tradecraft to advance American interests in a GenAI world. At the President’s direction, the Secretary of State should lead the United States government in developing a new model of statecraft and new global institutions for this purpose:

- Develop and implement “Platforms Statecraft” as an integrated, strategic effort, in concert with U.S. allies and partners, to build out the global technology platforms that underpin advantage in GenAI and other strategic technologies — from the telecommunications infrastructure (e.g., cell towers, satellite arrays, submarine cables), to the digital networks (digital payments, e-commerce), to the software and applications (AI), to standards and regulations, and beyond — in order to ensure that these platforms are governed by the transparent, rules-based principles of our open societies;

- Adopt new tools to capitalize on the transformative power GenAI can unlock to ensure the Department of State remains at the cutting-edge in leveraging technology to execute and achieve its mission; and

- Design and organize multiple layers of international regimes, institutions, and dialogues to ensure that governments, and the private sector as needed, can work together to mitigate against the highest consequence negative use cases of GenAI and support the broadest possible positive-sum applications GenAI offers. This must also include bilateral discussion between the two leading nations in this field — the United States and the PRC — to seek to preserve strategic stability over strategic risks GenAI may create.

Background and Near-Term Implications of GenAI for Foreign Policy

Fundamentally, American interests have remained consistent for the past century. The United States has, if imperfectly, sought a free, open, market-driven world governed by a respect for the rule of law — this was better for both Americans and others around the world, than an international system less free, less open, or more centrally-planned.5 American ingenuity and dynamism would be the engine that ensures our nation’s success. Neither the strategic competition with the PRC nor the global technology competition changes these foundational assumptions. With GenAI, the systemic foreign policy issue for the United States to consider is how to shape GenAI’s global use and function so that it reinforces these interests.

GenAI’s rapid global scaling sharpens the existing risks and opportunities in the global technology competition and foreshadows the disruptive power that emerging technologies will bring, with their corollary positive and negative impacts on foreign policy:6

- Digital freedom7 will need further reinforcement in the face of GenAI-amplified disinformation,8 though GenAI itself offers to unlock a new era of learning for people around the world.

- GenAI’s required compute power will heighten the criticality of global digital infrastructure, from data centers to the communications networks that connect them to edge devices, as well as the importance of who controls that infrastructure.9

- The network effects10 that amplify the utility of technology platforms mean that whoever can better provide a technology package around GenAI will sway key swing states to their side, attracting more users to more attractive and increasingly useful platforms.

“GenAI’s rapid global scaling sharpens the existing risks and opportunities in the global technology competition and foreshadows the disruptive power that emerging technologies will bring…”

- How the United States and the PRC incorporate GenAI into a substantive bilateral dialogue, given the scope and scale of GenAI’s impacts, will be a central factor for global peace and stability.

- The potential adversarial — and existential — risks GenAI creates will require new fora and dialogues for engagement with like-minded allies and partners, as well as potential rivals, to mitigate these risks.

In addition to such broad ramifications, GenAI also holds important applications for foreign policy and the Department of State’s practical operations. GenAI will transform the speed, efficiency, and efficacy of the day-to-day work of the Department of State and other government agencies:

- Large language models (LLMs) can provide readily accessible translation services, help draft memoranda, and provide immediate research support on any pressing international issue.

- A GenAI system trained on and source-grounded in the Department of State’s history of cables and diplomatic reporting could become an unrivaled oracle of information to guide international relations and negotiations.

- GenAI could accelerate visa review and processing, boost foreign policy departments and agencies’ regulatory compliance responsibilities with automated review systems, and provide analytic trends and information regarding geopolitical events and crises.

The State of Play at the Department of State

The Department of State (the Department) is beginning to build the institutional capacity to establish U.S. leadership on the global dimensions of technology competition. The creation of an Ambassador-at-Large and a Bureau of Cyber and Digital Policy,11 an Office of the Special Envoy for Critical and Emerging Technology,12 an Office of Critical Technology Protection,13 a Regional Technology Officer (RTO) Program,14 and other steps position the Department for the global tech competition, particularly vis-a-vis the PRC.

To advance its work around GenAI, the Secretary of State should lead the Department, alongside other government agencies, to take further steps to strengthen a whole-of-government integration of the domestic and foreign policy aspects of technology competition.

- The significant commercial, industrial, and regulatory policy dimensions of GenAI (and other emerging technologies) will require a truly whole-of-government approach to bring together disparate departments, authorities, talent, and tools to advance U.S. interests.

- Simultaneously, policymakers must appreciate the domestic and international interconnections that technology policy holds for national strategy. The absence of domestic regulatory policy will hinder the ability of the United States to align allied action on regulations. Conversely, the absence of global context in shaping our domestic regulations may disadvantage the U.S. private sector in a global competition.

The Department will also need to build its own requisite tech policy expertise for its staff and bring online new tools, tailored to its unique collection and possession of national security sensitive information.

- The new capabilities that GenAI and other emerging technologies offer will require the foreign policy workforce to build new skill sets around these tools. Mastering the present GenAI moment demands not only understanding how to use GenAI tools but also how their policy implications interweave with the geopolitics of microelectronics15 or advances in synthetic biology.16

- Some entrepreneurial foreign and civil servants have already begun experimenting with GenAI tools like ChatGPT.17 The Department should encourage creativity in how GenAI can address operational gaps in the Department’s mission and work. And as its workforce identifies its tech needs to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of its work, the Department will need to be agile and responsive in identifying the necessary policy changes and resource requirements to adopt new capabilities.

Way Forward

Technology has always been a source of national power and influence in geopolitics. Today, it has become the center of gravity in strategic competition, given its scope, scale, and pervasive impact on nations and individuals alike.18 In this regard, technology platforms – those that facilitate our digital interactions with machines, information, services, businesses, and each other – form the foundations of today’s digital world, as well as connect it to the physical one. Technology platforms are elements of power that matter strategically. Just as nations in prior eras competed over access to coal, steel, oil, and other resources that dictated power in the physical world, a similar competition already is underway around tech and the digital world.

We face today the terra incognita of a GenAI world and a global competition to chart the map of unexplored challenges and opportunities.

- For such a competition, the United States needs to develop and implement, with its allies and partners, a foreign policy approach to win the technology platforms that matter, such as advanced networks, next-generation computing, and GenAI and its applications. We call this “Platforms Statecraft.” To do this, the Department must modernize its tools to meet the opportunities and challenges it will face.

- The United States also must work with its allies and partners to shape global frameworks and institutions to manage GenAI’s challenges and opportunities. We will need to manage GenAI’s highest consequence risks, and find a way to do so with rivals who do not share our world view. We will also need to craft mechanisms alongside like-minded allies and partners to build out a vision for how GenAI and other emerging technologies can better enable our open societies to thrive – we call this the “DemTech” agenda. We propose two multilateral frameworks to manage both priorities, as well as a bilateral approach with the PRC to reinforce strategic stability around the highest consequence risks.

Platforms Statecraft

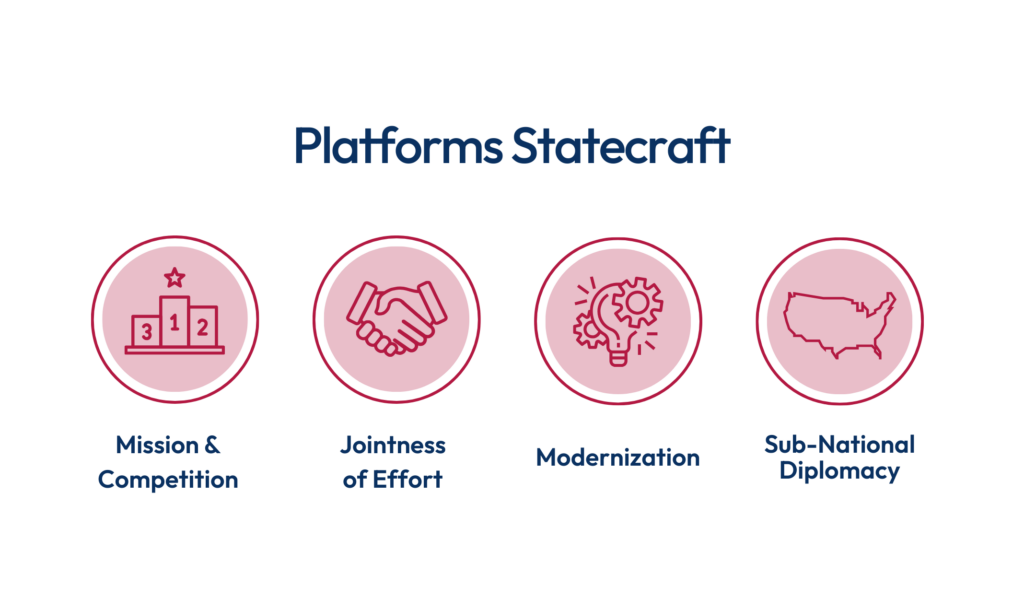

Platforms Statecraft19 should be built around the following elements: (1) mission and competition, (2) jointness of effort, (3) modernization, and (4) sub-national diplomacy.

- Mission and Competition. The U.S. government broadly remains structured to tackle the global counter-terrorism mission of the past 25 years. The United States needs a new mission statement to pivot U.S. foreign policy, with the Department at the lead, toward a new era of competition around technology platforms; a new “force posture” for U.S. foreign policy personnel and organizations to execute this new mission; and new or updated U.S. government and international institutions to advance a tech-focused mission.

- Jointness of Effort. Stovepiping in government is not new. Nevertheless, given the interlinked nature of domestic and foreign policy, as it relates to technology, the United States should seize on a new era of competition to break down as many silos as possible to build greater unity of effort toward a new mission. In short, a “Goldwater-Nichols”20 for foreign policy is needed to build more jointness in executing foreign policy across government agencies.

- Modernization. Diplomatic tradecraft will always entail a person-to-person connection. However, the Department’s foreign policy tools must keep pace with technological change, so it can bring to bear relevant technology expertise to advance American interests and relevant new tools to improve decision-making and deliver greater impact on the ground.

- Sub-National Diplomacy. If the private sector is the driver of American innovation,21 the United States needs to build a new strategic alignment between its public and private sectors to leverage the best of both in a global technology competition. This means a more robust infrastructure of sub-national diplomacy to ensure the Department and U.S. foreign policy are tied into domestic sources of innovation, including at the state and local levels, and can work hand-in-hand with domestic policy priorities.

Adoption of New Tools at the Department of State

GenAI tools will transform how the Department and the United States government operates by allowing the workforce to leverage tools to do their jobs faster — just as has happened with transitions from typists, to email, to Blackberries, and to Teams. GenAI tools do not take the agency out of policy makers in decision-making, but rather provide additional, and potentially novel, recommendations and solutions based on an amount of information that no one human can process as quickly as a machine.

The challenge with GenAI is the speed at which it is being adopted around the world — the United States government will have months, not years or decades, to adapt to the transformational capabilities these tools offer. The Department should move now to integrate GenAI to support its mission, and create channels for its workforce to help Department leadership identify tech needs that improve the efficiency and effectiveness of its work. The Department should also identify opportunities to work with allies to build out relevant joint capabilities. For instance, NATO’s recently launched Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic (DIANA) offers a platform to coordinate the development of a GenAI capability that all allies can use to advance their shared mission at NATO.

In addition to aforementioned applications, agency-wide programs to leverage GenAI that the Department can build out include:

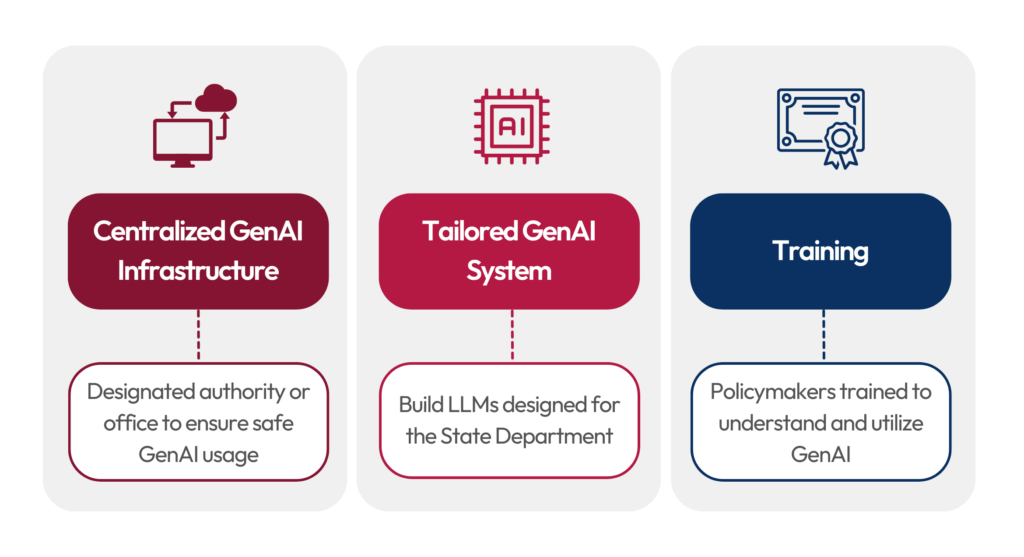

- A Centralized GenAI Infrastructure. To capitalize on GenAI’s promise, the Department needs a designated departmental authority to set the direction for safe GenAI usage. This authority should have the responsibility and resources to build and maintain an enterprise-wide IT infrastructure for the diversity of GenAI needs across the Department. This authority should also serve as the Department’s liaison with counterparts at other U.S. government agencies, to leverage GenAI for national security purposes.

- A Tailored GenAI System. Today’s leading LLMs demonstrate the potential to transform day-to-day work. The Department and other U.S. government agencies will need a system designed to handle sensitive and classified information. The Department should designate new skill codes and, as necessary, contract for the development, training, maintenance, and operation of a new GenAI system tailored to its specific needs. The system should be trained on the Department’s classified and unclassified databases holding cable traffic, internal deliberations, and policy decisions. The Department should conduct a security assessment on how and whether the system could operate on both unclassified and classified networks, or solely on a classified network.

- Training for Smart Employment of GenAI. GenAI tools should help transition time- and labor-intensive data aggregation tasks to machines, freeing the workforce to prioritize mission critical tasks, such as policy development and diplomatic engagement. Training policymakers to understand how these systems work and when and where to exert human oversight over these systems’ outputs will be a necessary step in adopting these systems.

Global Frameworks for Managing GenAI

We recommend a three-pronged approach to manage GenAI as a simultaneous geopolitical and transnational issue:

- A leaders-level forum that brings together key nations to address the highest consequence risks that GenAI may pose;

- A leaders-level agenda item on GenAI in bilateral U.S.-PRC dialogues to help the two nations manage associated strategic stability risks; and

- A working-level forum for like-minded nations to build out the positive use cases around GenAI and to mitigate against the practical challenges.

By setting a global governance floor against misuse, governments open the space for innovation to capitalize on GenAI’s wealth of opportunities.

1. Managing the Highest Consequence Risks: A Global AI Security Forum

Geopolitical competition will be a driver of escalatory GenAI risks. Nations — and affiliated non-state actors — seeking to advance their geopolitical interests may be tempted to unleash GenAI-enabled tools developed without guardrails that ensure their safe and ethical use. This heightens the chances of multiple forms of GenAI risk materializing, given the speed, scope, and scale at which potentially dangerous GenAI tools can operate, producing both intended and unintended consequences.22

The world requires a forum for capable actors to identify, dialogue on, and address emergent misalignment risks where evolving GenAI systems diverge from human intentions or control, leading to unintended consequences.23 A notional example of such risks would be early warning systems picking up erroneous threat signals based on aberrant patterns. This forum should also manage heightened threats emanating from the intersection of GenAI with the chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) domains as weapons of mass destruction.24 Establishing a new forum to address these issues must not preclude discussion through existing mechanisms with U.S. allies (e.g., NATO, G7, AUKUS) on our core national security interests. Nonetheless, a new entity is required to facilitate critical conversations among a wider set of necessary stakeholders if governance efforts are to be truly feasible.

At the President’s direction, the Secretary of State should lead the creation of a Global AI Security Forum (GAISF) focused on defining, placing, and ensuring guardrails around highest consequence GenAI risks.

- Membership: Participants should include leaders of nations and regional integration organizations with the capacity to significantly shape, determine, or use GenAI at a scope and scale that can cause or prevent a global cascading disaster. Initial members could include the United States, the PRC, the European Union, the United Kingdom, Russia, Israel, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, India, Brazil, the African Union, and the Gulf Cooperation Council.25

- Industry Engagement: The GAISF should also engage private sector actors, given their central role in driving GenAI innovation. The GAISF should invite private sector partners to join appropriate discussions and build appropriate mechanisms — such as advisory committees or working groups — to sustain dialogue between public and private sector participants.

- Coordinate with Existing Regimes: The GAISF should engage with existing international institutions with mandates to address CBRN risks, such as the International Atomic Energy Agency26 and Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons,27 as well as multinational initiatives supporting applicable provisions of international law.28

- Emergent Misalignment Risks: The GAISF should establish a stronger scientific and technical consensus as to the risks of AI systems escaping human control. An Intergovernmental Panel on AI Security (IPAIS)29 could convene academic, civil society, and private sector experts to assess this issue.30

- Set and Adapt Expectations: At its most ambitious, participating leaders could direct their governments to work toward creating an agreed set of governance guardrails against the highest consequence risks with GenAI. This could include mechanisms to monitor, verify, and enforce compliance in order to mitigate against or prevent these risks.31 At a minimum, the GAISF could serve the important purpose of informing leaders about unforeseen risks of which leaders may not be aware, or exposing malign activity of irresponsible actors.

2. Incorporating GenAI as an Agenda Item in U.S.-PRC Dialogues

Responsible world leaders engage in dialogue on issues of global importance. Particularly when engaging from a position of strength,32 leading powers recognize that dialogue can avoid precipitous slides into conflict, advance national interests, and further mutually beneficial resolutions of matters of common global concern. The United States and the PRC have a history of conducting strategic dialogues. The United States also has deep experience in conducting dialogues33 with a geopolitical rival – the Soviet Union – that kept the peace, unlocked strategic advantages, and even found points of collaboration.34 As the United States structures its channels of bilateral communication,35 the implications of GenAI should be a priority agenda item in appropriate channels with the PRC.

As the two leading countries in frontier large language model (FLLM) capabilities, the United States and PRC have a shared interest in understanding the strategic implications of and preserving strategic stability around the highest consequence risks of this novel technology. Dialogue can range from setting expectations around GenAI’s use in military settings36 to managing these tools’ societal impacts, particularly in those use cases that permeate across national borders.37 Conversations to clarify intentions and to avoid surprise, where possible, will become increasingly important to avoid unintentional escalations.

Bilateral dialogues that include GenAI should include a track 1.5 dimension to bring U.S. and PRC companies into the discussion. As with the cyber domain, it is often private actors that possess cutting-edge capabilities in GenAI.38 Their insights are crucial to informed, nuanced dialogue. Likewise, strategic stability discussions around GenAI will require making agreed guardrails and protocols clear to these private actors so that they do not inadvertently spur escalatory incidents.39

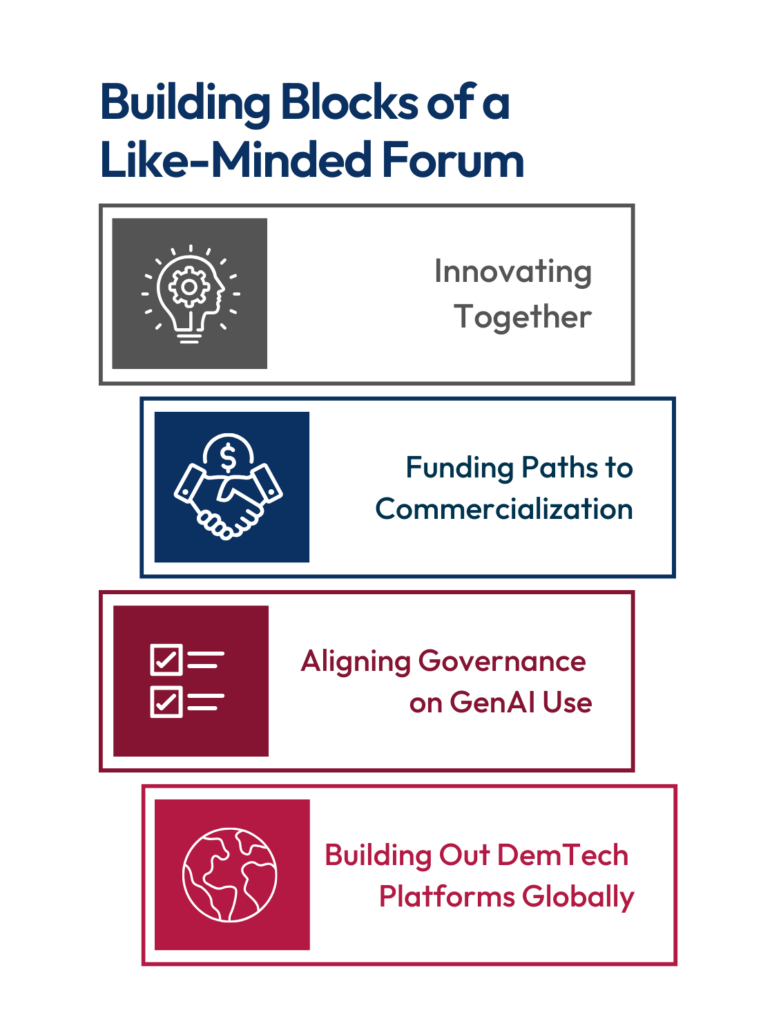

3. Building a Like-Minded Forum to Advance a New DemTech Vision

Mastering GenAI could provide a model for like-minded collaboration across several strategic “DemTech” battlegrounds.40 The United States and its allies and partners have a shared, vested interest in: innovating together; funding joint research and commercialization; governing emerging technologies in a more aligned manner; and building out technology platforms around the globe to protect and expand the DemTech ecosystem in an interconnected world. The recent G7 discussions41 offer a launching point for the United States and a core set of partners to create a cooperative DemTech forum to commence this work, beginning with GenAI.

This forum would facilitate:

- Innovating Together: The G7 nations and like-minded partners should reinforce pathways to collaborate on research and development driving cutting-edge innovation. Those opportunities should include both government-to-government partnerships42 and support for academic/private sector cooperation, beginning with STEM-focused exchanges.

- Funding Paths to Commercialization: In an international contest of technology platforms, research and development initiatives must move toward commercialization at global scale. That task demands funding projects not only in the United States, but also in allies and partners, alongside joint ventures. The Department of State should work with the Department of Commerce to convene investors from across the G7 and like-minded partner countries for opportunities to engage GenAI application developers seeking investment.

- Aligning Governance on GenAI Uses: The global expansion of DemTech platforms begins with harmonizing governance regimes so that GenAI models can operate in G7 and like-minded country markets in a manner consistent with democratic values and compatible with local regulatory requirements. To further this effort, the Department of State should establish a new G7 forum under the Hiroshima AI Process43 that would:

- Align standards and norms around data inputs in furtherance of accountability and transparency in GenAI models;

- Develop common rules on high-consequence use cases, such as the use of GenAI tools in critical infrastructure, law enforcement, national security operations, and election integrity;44

- Convene a multinational working group of experts from the G7 and like-minded countries that subscribe to the Hiroshima AI process/Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT) framework to determine violations and consequences for violations of these shared practices;45 and

- Explore a minilateral monitoring and verification regime for GenAI actors’ compliance with these shared practices.

- Align standards and norms around data inputs in furtherance of accountability and transparency in GenAI models;

- Building Out DemTech Platforms Globally: The United States and its allies and partners must cooperate to promote the reach and use of technologies developed in line with democratic values to the broader world. This task entails jointly facilitating new innovation partnerships with actors in the developing world, financing local uses of GenAI and the underlying digital infrastructure, supporting foundational educational efforts, and providing capacity-building tech and governance assistance.46 Accordingly, the Department of State should convene other relevant U.S. government agencies, allied counterparts, and private sector partners to:

- Support foundational development activities to strengthen local GenAI capacities and digital literacy programing to help build local skills to develop and use GenAI tools;47 and

- Support technical and regulatory assistance for Global South countries seeking to govern GenAI use cases and adopt their own models,48 including funding South-South exchanges for more tailored lessons on governance and entrepreneurship.

- Support foundational development activities to strengthen local GenAI capacities and digital literacy programing to help build local skills to develop and use GenAI tools;47 and

The GenAI world will reinforce the importance for the United States to lead and help shape a DemTech agenda, alongside allies and partners, to advance the interests of open societies against closed authoritarian systems. The United States, with its allies and partners, will need to preserve its advantages in the global technology competition and strengthen those areas where it is falling behind. Ultimately, the United States’ security and prosperity in a world defined by technological interlinkages and global impacts will depend on its ability to convince the widest range of nations to join a DemTech ecosystem grounded in respect for individual liberties, fair competition, and the rule of law.

Endnotes

- The United States has set both a strategic direction in two sequential National Security Strategies and begun to move in support of that strategy. See National Security Strategy, The White House (2022); U.S. National Security Strategy, The White House (2017); Pub. L. 117–167, CHIPS and Science Act (2022).

- National Security Strategy, The White House at 11 (2022); Derek Chollet, et al., Building “Situations of Strength”, Brookings Institution at 21-23 (2017).

- Mid-Decade Challenges to National Competitiveness, Special Competitive Studies Project at 16-27 (2022).

- Eric Schmidt, Innovation Power: Why Technology Will Define the Future of Geopolitics, Foreign Affairs (2023).

- National Security Strategy, The White House at 8-11 (2022). See generally, G. John Ikenberry, A World Safe for Democracy, Yale University Press (2022).

- Mid-Decade Challenges to National Competitiveness, Special Competitive Studies Project at 98-119 (2022).

- See Defending Digital Freedom and the Competition for the Future of the World Order, Special Competitive Studies Project (2022).

- Paul M. Barrett & Justin Hendrix, Safeguarding AI: Addressing the Risks of Generative Artificial Intelligence, NYU Stern School of Business at 8-9 (2023); Madison Fernandez, Fakery and Confusion: Campaigns Brace for Explosion of AI in 2024, Politico (2023).

- A battle over the world’s digital infrastructure is already well underway in many dimensions. See Joe Brock, Inside the Subsea Cable Firm Secretly Helping America Take on China, Reuters (2023); Jacob Helberg, Wires of War, Avid Reader Press at 91-94 (2021).

- What Is the Network Effect?, Wharton Online, University of Pennsylvania (2023).

- Press Release, Establishment of the Bureau of Cyberspace and Digital Policy, U.S. Department of State (2022).

- Establishing the Office of the Special Envoy for Critical and Emerging Technology, U.S. Department of State (2023).

- About Us – Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation, U.S. Department of State (last accessed 2023).

- Establishment and Expansion of Regional Technology Officer Program, 22 U.S.C. §10305 (2023).

- See Rob Tows, The Geopolitics Of AI Chips Will Define The Future Of AI, Forbes (2023); Chris Miller, Chip War, Scribner at 283-94 (2022).

- See Rebecca Sohn, AI Drug Discovery Systems Might be Repurposed to Make Chemical Weapons, Researchers Warn, Scientific American (2022).

- Alexander Ward, et al., Shaheen to Admin: Get Me the Black Sea Strategy, Politico: National Security Daily (2023) (“At least one U.S. embassy [Embassy Conakry] already is using ChatGPT for its public diplomacy products…”).

- Mid-Decade Challenges to National Competitiveness, Special Competitive Studies Project at 22-23 (2022); See also Harnessing the New Geometry of Innovation, Special Competitive Studies Project at 10-14 (2022).

- A forthcoming, dedicated report on reforming foreign policy for technology competition will build out these recommendations in detail.

- See James R. Locher III, Victory on the Potomac: The Goldwater-Nichols Act Unifies the Pentagon, Texas A&M University Press (2004).

- In 2018, the private sector funded 70 percent of U.S. research and development, while the federal government funded only 22 percent. See Melissa Flagg & Paul Harris, System Re-engineering: A New Policy Framework for the American R&D System in a Changed World, Center for Security and Emerging Technology at 4 (2020).

- See Bill Drexel & Hannah Kelley, China Is Flirting With AI Catastrophe, Foreign Affairs (2023).

- Geopolitics is a potential key driver of risky behavior that could yield existential challenges, but it is not the only one. As the 2022-2023 release of U.S.-based LLMs illustrates, regular market pressures can push actors to run fast and push boundaries without developing corresponding guardrails or controls. See Kevin Roose, How ChatGPT Kicked Off an A.I. Arms Race, New York Times (2023). International efforts to mitigate geopolitically-driven existential risk must be paired with complementary rules/guardrails around private actors competing commercially.

- SCSP has proposed a new Forum on AI Risk and Resilience (FAIRR) grounded in the G20 as a complementary recommendation focused on managing transnational GenAI-enhanced risks at the regulator level. Given the complexity and overlapping issues involved in GenAI governance, multiple lines of effort addressing different vantage points is a preferable option. See Gabrielle Sierra & Sebastian Mallaby, AI Meets World, Part Two, Why It Matters, Council on Foreign Relations at 18:53 (2023).

- Particularly, U.S.-PRC trust levels in this space are low. The PRC is as, if not more, concerned about geopolitical risk from the United States as existential GenAI risk. Dake Kang, Cooperation or Competition? China’s Security Industry Sees the US, Not AI, as the Bigger Threat, Associated Press (2023). Likewise, the United States would be entering discussions cognizant of past PRC divergence from cyber/digital agreements. See U.S. Accuses China of Violating Bilateral Anti-Hacking Deal, Reuters (2018).

- See History, International Atomic Energy Agency (last accessed 2023); Statute, International Atomic Energy Agency (last accessed 2023).

- See Mission, Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (last accessed 2023).

- In addition to formal international institutions, nations have flexible minilateral regimes to create effect, such as the Proliferation Security Initiative. The Proliferation Security Initiative, PSI (last accessed 2023). In some cases, international agreements — like the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention — are monitored and enforced by coordinated national efforts. See Filippa Lentzos, Compliance and Enforcement in the Biological Weapons Regime, United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research at 1 (2019).

- The IPAIS could draw on the model of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. About the IPCC, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (last accessed 2023). See also Nicolas Miailhe, Why We Need an Intergovernmental Panel for Artificial Intelligence, UN University: Our World (2019).

- Deploying the IPCC model in a narrow lane on this subject avoids the critique that an IPCC model that restricts broad AI development and deployment until the panel renders its assessment would overly restrict humanity’s ability to adopt AI tools in the near-term. See Eline Chivot, French Proposal for an “IPCC of AI” Will Only Set Back Global Cooperation on AI, Center for Data Innovation (2019).

- Monitoring, verification, and enforcement of GenAI’s risks, from practical to highest consequence, will require a new doctrinal approach to better understand the nature of real risks of harm to humans that GenAI systems can create, the cascading nature of these harms to larger human populations, the constituent capabilities that underpin GenAI systems, and how and whether these capabilities can be effectively monitored and controlled. Existing institutions such as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) offer useful, though imperfect, models for what a new institution to address GenAI risks can look like.

- Dean Acheson, Present at the Creation, W.W. Norton at 378 (1969).

- See U.S.-China Comprehensive Economic Dialogue, U.S. Department of the Treasury (2017); 2016 U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue, U.S. Department of State (2016).

- See Hal Brands, The Twilight Struggle, Yale University Press at 130-150 (2022).

- Press Release, Readout of Secretary Raimondo’s Meeting with Minister of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China Wang Wentao, U.S. Department of Commerce (2023); Kaanita Iyer, Blinken Says US is ‘Working to Put Some Stability’ into Relationship with China, CNN (2023); Keith Bradsher, 3 Takeaways From Janet Yellen’s Trip to Beijing, New York Times (2023); Demetri Sevastopulo, CIA Chief Made Secret Trip to China in Bid to Thaw Relations, Financial Times (2023).

- See Jacob Stokes, et al., U.S.-China Competition and Military AI, Center for a New American Security (2023).

- See Paul Sampson, On Advancing Global AI Governance, Centre for International Governance Innovation (2023).

- See Harnessing the New Geometry of Innovation, Special Competitive Studies Project at 22-29 (2022).

- Limitations on private actors for international stability reasons could be similar to the “no hack-back” rules that the United States currently applies to private cyber actors. See James Rundle, Letting Businesses ‘Hack Back’ Against Hackers Is a Terrible Idea, Cyber Veterans Say, Wall Street Journal (2021).

- SCSP has identified six technology battlegrounds that democracies must lead in to shape the future in line with the values and interests of the democratic world: (1) AI; (2) novel microelectronics and computing paradigms; (3) next-generation networks; (4) biotechnology; (5) new energy generation and storage; and (6) smart manufacturing. Mid-Decade Challenges to National Competitiveness, Special Competitive Studies Project at 170-81 (2022).

- See Fact Sheet: The 2023 G7 Summit in Hiroshima, Japan, The White House (2023).

- See Strengthening and Democratizing the U.S. Artificial Intelligence Innovation Ecosystem An Implementation Plan for a National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource, National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource Task Force (2023).

- G7 Hiroshima Leaders’ Communiqué, The White House (2023).

- This forum could be harmonized with the G7’s Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT) initiative, as data privacy and security are core inputs to GenAI models. Overview of DFFT, Japanese Digital Agency (last accessed 2023); G7 Digital and Tech Track Annex 1: Annex on G7 Vision for Operationalising DFFT and its Priorities, G7 (2023).

- At best, these higher-level standards and norms may become the seed of wider global governance practices. At a minimum, these agreements can serve as mutually agreed to redlines among forum members for action against external malign actions, akin to the Tallinn Manual in cyberspace. See Tallinn Manual 2.0 on the International Law Applicable to Cyber Operations, Cambridge University Press (2017); Michael Schmitt, Tallinn Manual 2.0 on the International Law of Cyber Operations: What It Is and Isn’t, Just Security (2017).

- Without directly comparing GenAI as a technology to the nuclear revolution, there is precedent of the United States providing technical and governance support to enable other countries to safely adapt new technologies. See Peter Lavoy, The Enduring Effects of Atoms for Peace, Arms Control Today, Arms Control Association (2003).

- See Michael Trucano, AI and the Next Digital Divide in Education, Brookings Institution (2023).

- One example of a program worth exploring scaling in the Global South is the German government’s “FAIR Forward” initiative. See Open Data for AI, BMZ Digital.Global (last accessed 2023).