Strong economic foundations enable societies to thrive and provide the resources for nations to sustain technology leadership, craft a competitive foreign policy, and project military power. While the United States holds the upper hand across a number of economic fundamentals,1 China’s techno-economic advance is testing whether America can continue to translate its advantages into national power without changing course. The PRC’s economic size, second only to the United States in market terms,2 and ability to project economic power globally make it an unprecedented rival — larger and more powerful than the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Beijing has put the coercive power of the state at the forefront of its economic strategy, claiming that its Leninist, single-party dictatorship is better equipped than democracies to invent the future.3 Massive government support for domestic industry, coupled with rampant technology theft abroad and other unfair policies, have wiped out jobs, companies, and entire industries and suppressed innovation in advanced economies. 4

The economic competition is America’s to lose. The United States holds massive advantages, including the world’s largest and most liquid financial markets, the dollar’s status as the global reserve currency, and a diversified and resilient economy that has a strong track record of bouncing back from downturns. Additionally, a worldclass innovation ecosystem, a highly productive labor force, the ability to attract global talent, and trusted legal and regulatory institutions make the United States the world’s most dynamic economy.5 More than any other nation, American capital builds prosperity around the world in the form of foreign direct investment (FDI).6 America can significantly amplify its advantages by working with allies, as democracies account for more than 60 percent of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP).7

But there are storm clouds on the horizon. The United States is falling behind in advanced industries, including high-capacity batteries and microelectronics.8 Decades of hands-off economic policies have accelerated the outsourcing of American manufacturing to East Asia.9 The U.S. technology sector, left on its own and driven by short-term imperatives to reduce labor and capital expense, has skewed heavily towards software and services, leaving America with critical vulnerabilities in hardware production.10 The United States now finds itself unable to manufacture critical goods that it needs, and brittle supply chains leave the country vulnerable to supply shocks.11

Beijing has put the coercive power of the state at the forefront of its economic strategy, claiming that its Leninist, single-party dictatorship is better equipped than democracies to invent the future.

A Techno-Industrial Strategy should build on America’s fundamental strengths to boost economic output and fill national security gaps, yielding spillover benefits for the entire economy.

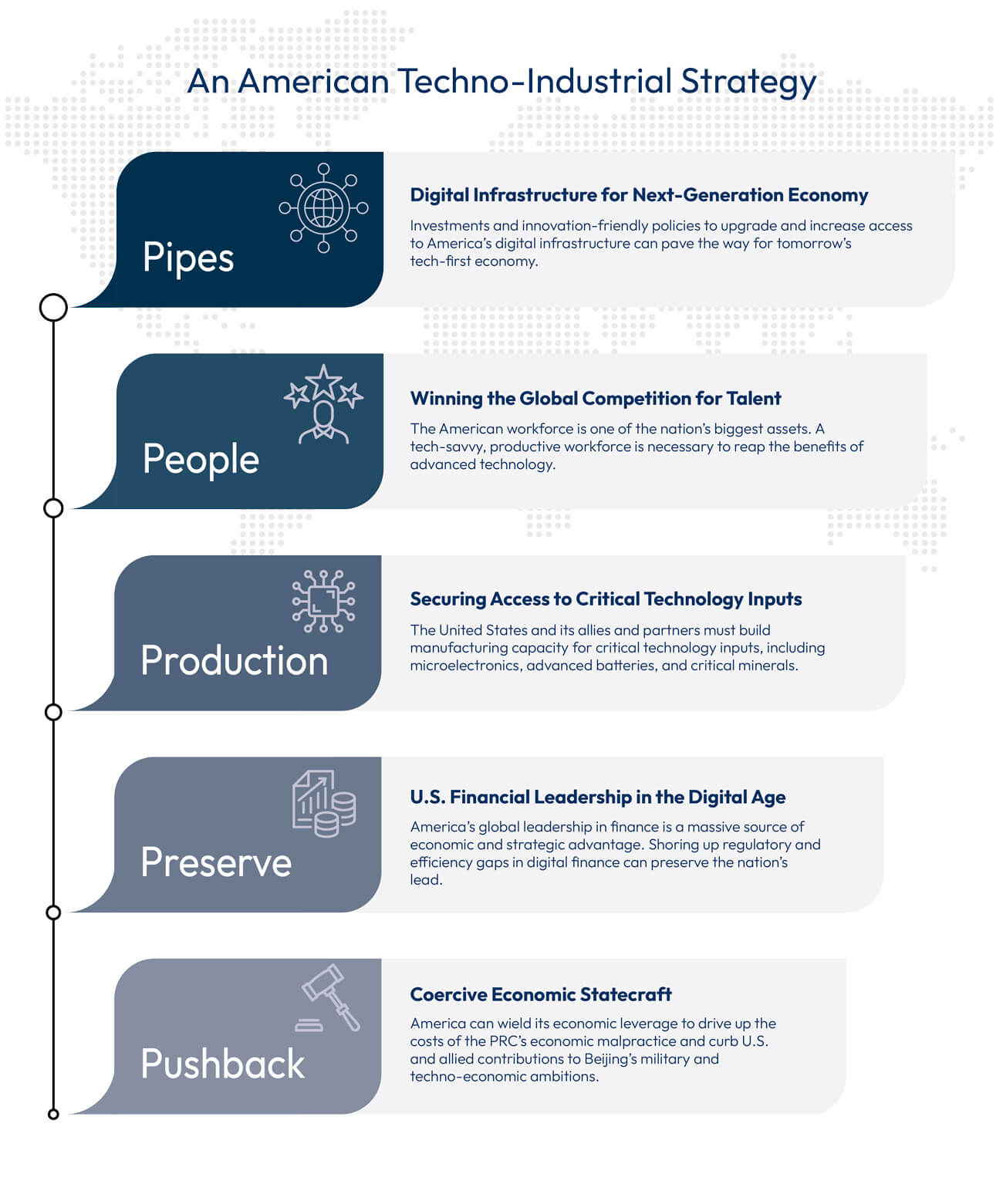

The United States must respond by crafting a Techno-Industrial Strategy (TIS)12—an industrial strategy focused on cutting-edge technology sectors that drive economic growth and are critical for national security. A Techno-Industrial Strategy should build on America’s fundamental strengths to boost economic output and fill national security gaps, yielding spillover benefits for the entire economy.13 Though some maintain that industrial strategy is inefficient, harmful, and runs counter to free market principles,14 targeted intervention can generate wealth and fill gaps when the market falls short.15 A TIS should focus on two objectives:

- Encourage Technology Diffusion. To stay ahead, the United States must scale emerging technologies like microelectronics, 5G, and AI more quickly. Moving technologies from the lab to the market boosts economic output, creating national wealth and improving livelihoods. Economists recognize a role for the government in funding research and development (R&D) and scaling emerging technologies through workforce and infrastructure investment—areas where the market tends to fall short.16

- Fill Economic and National Security Gaps. Running faster will not be enough to stay ahead. The United States must close critical supply chain vulnerabilities, preserve global financial leadership, and ensure that its technological innovations and capital do not fuel PRC military capabilities or techno-economic malpractice.

A TIS must include the following lines of effort:

Toward a Techno-Industrial Strategy

Industrial strategy is part of the American experience. Throughout its history, the U.S. Government has responded to times of strategic competition and national emergency by partnering with the private sector to correct market failures and fill critical technology gaps.17 In recent decades, policymakers have overlooked America’s history of leveraging public-private partnerships to push the technological frontier and promote diffusion. Today, however, industrial strategy is enjoying a resurgence. The White House has called for a “Modern American Industrial Strategy,”18 and President Biden signed into law the CHIPS and Science Act, a $280 billion spending package to revive American innovation that includes $52 billion for semiconductor production and research.19 Washington should build on this traction by providing incentives and making investments in strategic technologies to ensure America remains ahead, drawing on lessons from the past.

The United States has a long history of employing industrial strategies to boost national advantage. In 1791, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton submitted his Report on the Subject of Manufactures to Congress proposing a slate of measures to support manufacturing in strategic industries.20 Hamilton’s vision was realized a few decades later under the American System, an industrial strategy that included subsidies to build railroads, canals, armories, and other forms of infrastructure.21 Abraham Lincoln advanced this strategy by signing legislation that chartered the Transcontinental Railroad and established a system of land grant colleges.22 By the early 20th century, the United States had emerged as a global power. Industrial strategy projects—including World War II mobilization and Cold War-era government interventions that jump-started the microelectronics industry—strengthened the country’s techno-economic foundation, readying it for strategic rivalries with Germany, Japan, and later with the Soviet Union.23

Well-crafted industrial strategies encourage—not stifle—competition among firms. Establishing market conditions is the best way for the government to foster competition. Opponents frame industrial strategy as the government’s attempts to “pick winners.”24 However, successful industrial strategies can create market conditions that do not naturally exist, allowing firms to compete to meet the national demand.25 The government can jumpstart markets by setting high technical “bars,” accompanied by results-oriented metrics, and rewarding entrepreneurs who meet them.26 Operation Warp Speed, a public-private partnership initiated by the White House, followed this template and fielded COVID-19 vaccines in a record 10 months.27

Pipes: Digital Infrastructure for a Next-Generation Economy

Technologies driving 21st-century economic growth, like artificial intelligence, rely on digital infrastructure—including 5G networks, satellite arrays, and IoT devices—to connect and power them. The United States can pave the way for an AI-driven society and economy through swift investment in secure domestic digital infrastructure, removing regulatory hurdles, and forming public-private partnerships to foster private sector-driven innovation. Ensuring rapid diffusion of digital technologies will promote broad-based growth and offer secure, speedy links to all Americans.

The United States should move quickly to build out secure digital infrastructure for broadband access, 5G networks, satellite arrays, and IoT edge devices to reach businesses and citizens across America. With tens of billions of dollars already appropriated for a nationwide broadband rollout, the focus now must be on rapid, maximum-impact execution, optimizing for both network security and procurement cost.28 The Federal Communications Commission should set more ambitious deadlines and adequately fund federal requirements for telecoms and Internet service providers to implement “Rip and Replace” rules to remove PRC-made Huawei and ZTE components.29

U.S. authorities should implement policies to expand public and private 5G network reach. Wired optical networks will underpin digital connectivity, but the development of 5G and 6G fixed-wireless access, low-Earth-orbit satellites, and other technologies can offer competitive alternatives for last-mile broadband, especially in underserved communities. The U.S. Government should make more radio spectrum available to commercial users—not only for telecom networks, but also for smaller firms and private 5G networks and Open Radio Access Network (O-RAN) testbeds—and improve the spectrum allocation process.30

The U.S. Government should accelerate R&D and remove barriers for distributed innovation of commercial 5G applications, industrial testbeds, smart cities technologies, and O-RAN architectures, setting out a bold strategy for a “smart society.” 5G cellular networks promise to unlock commercial and public sector applications in smart manufacturing, smart cities, and other uses foundational to the next generation economy.31 While PRC firms Huawei and ZTE surged ahead of U.S. competitors in developing and deploying certain 5G network technologies and components,32 no single firm or country has won the still-ongoing race to develop new 5G applications, many of which are yet to be developed.33 Government should partner with the private sector and create sandboxes to drive development and testing of these applications so America becomes a market leader and standards-setter for 5G applications.34 U.S. authorities should incentivize and fast-track development and deployment of flexible O-RAN and virtualized network architectures, which can create opportunities for more U.S. tech firms, lead to lower network costs, and foster U.S. leadership in international standards setting.35

…no single firm or country has won the still-ongoing race to develop new 5G applications, many of which are yet to be developed.

The United States should forge a national data strategy to leverage, securely, America’s data as an asset for its innovators. The initiative should foster responsible artificial intelligence applications while protecting digital privacy and security. A U.S. data strategy should aim to serve citizens, boost economic growth, and provide a model of democratic, innovation- friendly data governance. The strategy should articulate clear, consistent personal data privacy rights and plan how best to harness data to spur private sector-driven innovation and growth, including responsible AI development. The federal government should make data and cloud computing available to small firms as well as academic researchers and non-profit organizations via a National Research Cloud.36 Creating a clear strategic and regulatory framework for data can offer a positive template for other countries, which currently may look to either China or the EU for models, and lay the groundwork for increased international digital trade and trade agreements based on responsible, open Internet norms.

The U.S. Government should invest in and integrate cybersecurity measures throughout the nation’s digital infrastructure in partnership with private sector and non-profit partners. Authorities should collaborate with technology firms to identify and neutralize threats and vulnerabilities swiftly.37 One area deserving new focus is the need to address vulnerabilities in non-proprietary open source software and hardware, which are both expanding.38 A way for the government to address such vulnerabilities could be for Congress to authorize the creation of a Center for Open Source Technology Security to identify and catalog technology in need of support and fund critical improvements.39

People: Winning the Global Competition for Talent

Developing, scaling, and adopting emerging technologies—and reaping their economic benefits—requires a productive and tech-savvy workforce.40 Today, however, the United States is not producing or recruiting the technical talent it needs.41 Although interest in emerging technology fields has skyrocketed, the U.S. education and immigration systems are struggling to meet demand.42 Nearly one-third of American adults have limited or no digital skills.43 These gaps pose a major threat to U.S. economic competitiveness and national security. In partnership with the private sector and academia, Congress and the Executive Branch must take bold action to advance effective education, immigration, and workforce development policies.

- Education

The federal government must heavily invest in STEM and emerging technology education. The NSCAI recommended a National Defense Education Act (NDEA) II and a U.S. Digital Service Academy (USDSA).44 Modeled on the original post-Sputnik legislation, NDEA II would provide landmark investments for students focused on acquiring digital skills, including computer science, data science, information science, mathematics, and statistics. USDSA would be an accredited, degree-granting university that produces government civilians with digital expertise to serve across the U.S. Government’s departments and agencies.45 The James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 proposes a Department of Defense (DoD) Cyber and Digital Service Academy Scholarship.46 To address the broader talent shortage, America will need an established academy, and a concerted national effort with education, to provide the scale needed to help close the tech talent gap in government. Current scholarships and programs cannot match the growing demand for talent in government agencies, meaning bold action is required.

The federal government should expand partnerships between industry and academia and leverage apprenticeship programs to train, reskill, and upskill the next generation of emerging technology talent. Developing a tech-savvy workforce will require utilizing and retraining current tech talent to develop cutting-edge programs in universities and community colleges.47 Building on the workforce development provisions in the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, federal and state governments should incentivize universities and colleges, and tech companies, to educate the future workforce in critical fields and scale existing programs.48 In addition, the federal and state governments could expand and tailor tax incentives offered to firms for worker training and apprenticeship programs in strategic industries like semiconductor packaging and battery assembly. These programs can be more cost-effective for companies compared to tuition assistance for workers.49

Congress and the Executive Branch must take bold action to advance effective education, immigration, and workforce development policies.

- Immigration

The U.S. Government should accelerate immigration processes, increase efforts to attract international tech talent, and target visas directly to needed tech fields. Highly-skilled immigrants have a disproportionately positive impact on innovation and job creation.50 In AI and other emerging fields, the United States is competing for a limited pool of talent spread around the world. Proposals such as the Million Talents Program51 to attract and retain one million “tech superstars” are examples of the bold action America needs to take. The United States should fast-track green cards and visas for workers in strategic sectors and create a separate, targeted “Innovator” visa category.52

The United States should ensure it remains a magnet for tech talent from the PRC and elsewhere, while implementing common sense precautions to protect national security. Students from the PRC and elsewhere with legitimate purposes for coming to the United States should continue to be welcomed. The Department of State should continue to filter out applicants with demonstrated national security risk factors, such as affiliation with the People’s Liberation Army, the PRC’s military-civil fusion (MCF) strategy,53 or talent programs, such as the Thousand Talents Plan, known to be CCP conduits for illicit tech transfer.54 Despite criticism that such safeguards cost the United States significant tech talent,55 the most prominent such policy—the 2020 Presidential Proclamation suspending entry for some students and researchers connected to MCF—has affected a very small minority of PRC student visa applicants.56

Strengthen research security. To balance the benefits of international collaboration with the need to protect sensitive intellectual capital from foreign threats, universities and research institutions should develop systems that require disclosure of potential conflicts of interest of researchers and funding organizations.57

- Workforce & Automation

The United States should invest in automation, as well as training for workers impacted by these technologies, to boost productivity and improve job quality. America should pursue productivity-boosting automation applications. Targeted investments and training can help to mitigate potential displacement and encourage technologies that support American workers. Automation can augment America’s workforce, enabling workers to acquire new skills and shift away from dangerous, unsanitary, or repetitive tasks.58

Production: Securing Access to Critical Technology Inputs

A techno-industrial strategy must also address gaps that pose strategic-level risks to economic and national security. Over the past several decades, policies based on market fundamentalism—the belief that unrestricted free trade and minimal government intervention is always the best policy—have incentivized companies to offshore critical manufacturing, resulting in an imbalanced U.S. economy with advantages in software. But critical vulnerabilities in hardware leave the nation exposed to supply shocks.59 The United States can fill these gaps, but only if the government is willing to shoulder more of the risk.

The U.S. Government must work with the private sector, and with its allies and partners, to build production capacity for critical inputs to dual-use technologies. The United States should prioritize securing supply of the following high-risk inputs:

- Rare Earth Minerals & Permanent Magnets: China controls about 85 percent of rare earth processing.60 The PRC has threatened to cut off America’s supply of rare earths, which are used in everything from iPhones to jet fighters (a single F-35 requires over 900 pounds of rare earths).61 Rare earth permanent magnets are used to build green technologies and precision-guided munitions.62

- Advanced High-Capacity Batteries: America relies on the PRC for green technologies, including advanced batteries that power electric vehicles and store clean energy.63 China controls about 80 percent of battery production.64

- Microelectronics: Semiconductors are the brains of modern technology. 100 percent of advanced chips are produced in Asia, leaving the U.S. supply vulnerable.65

Each of the industries listed above is critical to U.S. economic and national security, but all stand at risk of supply shocks due to military crises, public health emergencies, natural disasters, or other contingencies. We selected them based on four criteria: dual-use status,66 steep barriers to entry,67 economic importance,68 and adversary dependence.

In the short term, America must accelerate aggressive stockpiling efforts to ensure sufficient supply of rare earths and other critical minerals in the event of a conflict. Stockpiling can buy time for the United States to increase critical mineral production or shift supply chains in the event the PRC cuts off supplies. In 1975, the United States created the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to hedge against major oil shortages caused by supply shocks in the Middle East.69 To secure access to today’s strategic resources, the DoD should lead an aggressive stockpiling effort to guarantee rare earth and magnet supply to major defense programs by 2025.70 Once supply for defense platforms is guaranteed, the United States should stockpile minerals and magnets for green technologies. For non-defense needs, the United States should explore friend-shoring supply chains with trusted partners and create localization plans to create regional economies of scale.71 A good example of this is the United States partnering with other countries to diversify mineral supply chains, jointly offering countries in Africa, Latin America, and elsewhere a better value proposition for mining and processing contracts than PRC-backed competitors.72

The United States should invest in next-generation battery technologies to offset China’s dominance in lithium-ion technology. Lithium-based batteries are expensive73 and cells are difficult to transport due to safety concerns.74 Investing in new forms of non-lithium battery technology, such as molten-salt batteries, offers a potential opportunity to leapfrog the PRC’s bet on aging lithium-ion technology and reduce dependence on critical minerals produced and processed in China.75

Regaining American Leadership in Microelectronics

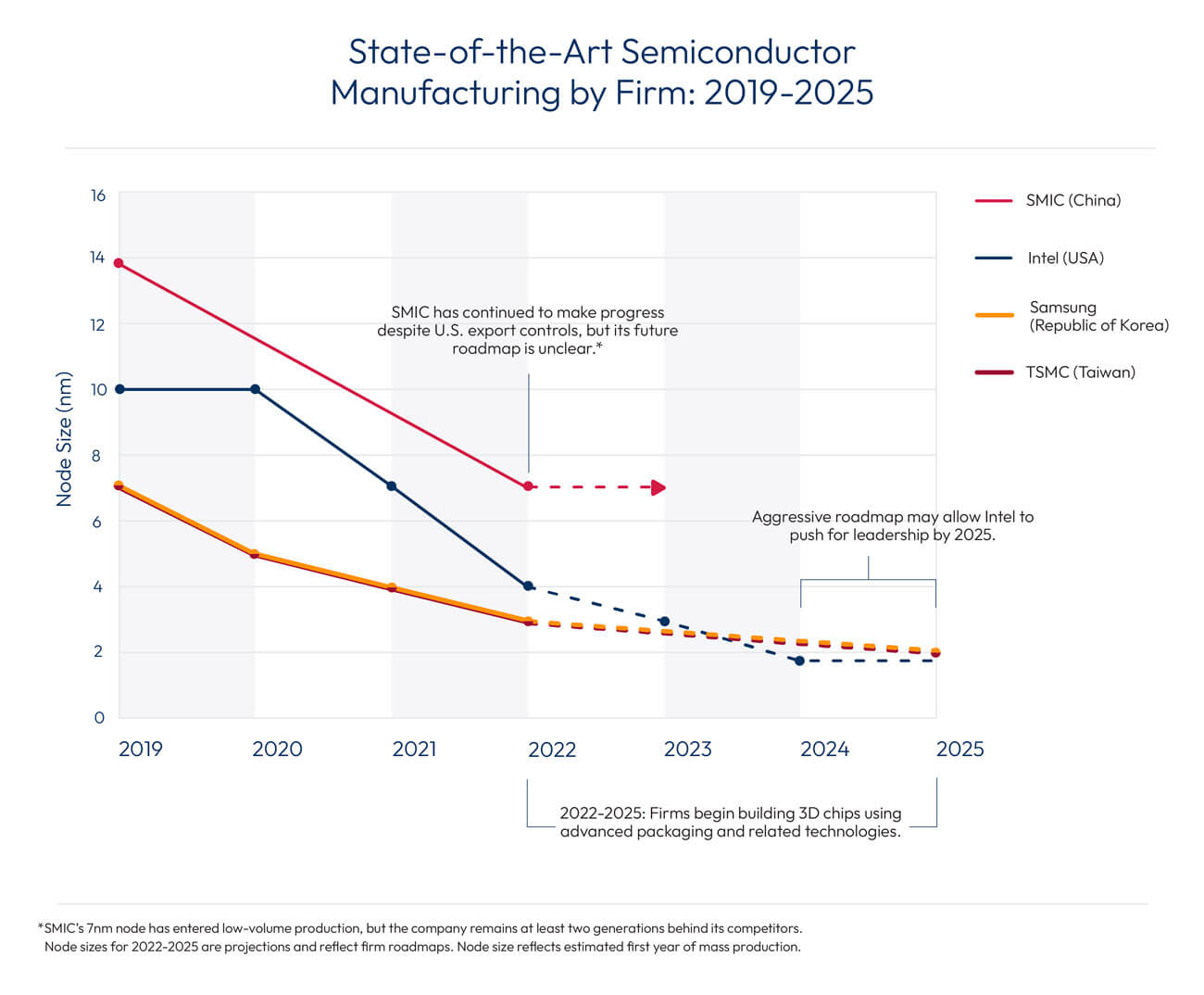

The United States does not currently produce any leading-edge chips, but two trends have created a critical mid-decade window to address this gap.76 First, semiconductor giants Intel, Samsung, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) each have begun constructing leading-edge fabs in the United States, though their scale and success depends in part upon the incentives provided by the CHIPS and Science Act.77 An accelerated implementation plan would increase the odds of success. Given higher building and operating costs, long-term incentives—especially tax provisions—are necessary to ensure America remains competitive in semiconductors through 2030.78 Second, Intel’s aggressive roadmap may potentially allow it to compete at the leading-edge with Taiwan-based TSMC and South Korea-based Samsung by 2025.79

The United States runs the risk of building semiconductor fabs but not having enough engineers to run them. Federal funding can help address this gap. America must invest in its microelectronics workforce.80 The country could face a talent gap upwards of 70,000 chip workers in the coming years,81 and chipmakers have identified this gap as a core obstacle to expanding their U.S. operations.82 Federal incentives can help the nation address this shortage.83 The CHIPS and Science Act includes $200 million to jump-start workforce training, but meeting demand will require sustained funding beyond this initial infusion, as well as additional H1-B visas for foreign engineers.84

The United States must ensure that post-Moore’s Law chips are designed and built in America. Policymakers should provide incentives to chip startups working to invent the future. As the chip industry nears the end of Moore’s Law, the breakthrough that pushes computing to a new paradigm may well come from a startup, rather than an established player. But compared to other industrialized nations, the United States is an unfriendly place for new chip firms.85 Policymakers should leverage the CHIPS and Science Act to lower costs and barriers to entry for semiconductor startups. The United States should focus on programs that make it cheaper and faster to transition from prototyping to high volume manufacturing.

American companies, and those in allied nations, have enabled the PRC’s chip breakthroughs. The United States and its allies must take stronger actions to block Beijing’s access to advanced chips. China is powering its AI ambitions and military modernization with advanced chips designed and built by firms based in the United States and allied countries.86 Policymakers must keep export controls and other policies current to the technology and threat, then place the onus on firms to demonstrate that sales of cutting-edge chips to the PRC do not boost Beijing’s military modernization and human rights abuses. Meanwhile, the United States has worked with the Netherlands to cut off supply of specialized extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV) machines to PRC firms,87 but these measures are not enough to slow down Beijing’s drive for self-sufficiency.88 In coordination with allies, the United States must block China’s access to semiconductor manufacturing equipment and restrict the transfer of expertise, know-how, and capital that helps PRC chip startups reach scale.89

Preserve: U.S. Financial Leadership in the Digital Age

America’s global leadership in finance is a key pillar of its national power, underpinning the prosperity of U.S. businesses and everyday Americans, as well as Washington’s ability to impose sanctions and shape global markets. The race to invent the future of money through digital currencies and payments platforms is also a race to preserve this vital advantage, set international payment and data standards, and determine whether democratic values govern the global financial system. The U.S. dollar maintains significant institutional and structural advantages that the renminbi is unlikely to displace in the medium term.90 However, U.S. fiscal, monetary, and regulatory missteps, combined with a concerted push by the PRC, could undermine confidence in U.S. financial leadership and lead to a fragmented global financial system.

The United States must lead in financial technology innovation to maintain the primacy of the U.S. dollar. The emergence of new financial technologies (fintech) – such as Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), cryptocurrencies, and payment systems – raises questions as to the long-term dominance of the U.S. dollar. Fintech could have considerable implications for illicit finance, regulatory regimes, traditional intermediaries (such as banks and brokers), and systemic financial risk. To strike the right balance between innovation and risk mitigation, the United States should create regulations governing cryptocurrency-related digital security, liability, and business and disclosure practices that provide clarity to investors and innovators and ensure financial stability, transparency, and consumer protections. A clear, innovation-friendly regulatory regime can also guide international standards for use and regulation of cryptocurrencies.

The United States should improve the efficiency of dollar-based payments infrastructure to counter the PRC’s renminbi-based electronic payments platforms. The PRC has set its sights on undermining the dollar’s dominant role in global finance.91 Without a flexible exchange rate, an open capital account, and widely trusted public institutions, the PRC will struggle to establish the renminbi as a global reserve currency rivaling the dollar, or even its nearest peers including the euro, yen, and pound sterling.92 At the same time, Beijing’s efforts could erode the dollar’s position in settling international transactions and hand the PRC a first-mover advantage in setting standards for digital finance and related data platforms. The PRC is deploying currency innovations, like the electronic renminbi (e-CNY), and renminbi-based alternative payment channels, such as the Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS)93 to increase transaction efficiency, reduce vulnerability to U.S. sanctions, and harvest data at home and abroad.94 The United States can support innovations that reduce transaction costs and improve efficiency and resilience in dollar-based and U.S.-led payment systems, such as those run by the Federal Reserve,95 the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), and the Clearing House Interbank Payment System (CHIPS).96

The U.S. should seek to set international standards and regulations for Central Bank Digital Currencies and dollar-pegged stablecoins that align with democratic values and preserve financial stability. CBDCs – digital forms of money issued and backed by a central bank97 – and stablecoins – privately issued digital currencies with an exchange value pegged to a fiat currency – carry potential benefits and risks. While they could improve inclusion and efficiency within the financial system and even deepen the dollar’s global role, they might also create new cybersecurity, privacy, and financial stability vulnerabilities. As the PRC pilots its own autocratic CBDC98 initiative, the United States has a unique opportunity to set international standards for CBDCs and stablecoins compatible with democratic values, allowing private sector innovators to compete to develop the best technical solution for a CBDC within those parameters.

The United States could establish a National Security Commission on Digital Finance (NSCDF) to study the impact of digital finance on national security and economic competitiveness. The subject of digital finance combines many individually complex topics: banking, technology, monetary policy, geopolitics, data privacy, and data sovereignty issues. Building on the ongoing policy processes mandated by the Executive Order on Ensuring Responsible Development of Digital Assets99, an NSCDF could convene private stakeholders and public officials to present findings and make recommendations to the President and Congress on digital finance.

Intellectual Property Rights: A Cornerstone of the Innovation Economy

As emerging technologies produce new forms of value, the United States should update its intellectual property (IP) regime to keep up. Robust IP rights underpin the U.S. economy’s vibrant innovation ecosystem and incentivize value creation. Yet the United States has not modernized IP laws and policies to keep pace with rapid innovations in AI, fintech, biotechnology, and other sectors. To address this gap while safeguarding U.S. national security and promoting economic competitiveness,100 four areas should be prioritized:

- Determine whether AI that generates inventions and creations should be entitled to IP protection.

- Clarify the current patent eligibility doctrine that has created enormous uncertainty surrounding patent protections for cutting-edge computer-implemented and biotechnology inventions. A lack of clarity deters investments in high-risk innovation.101

- Examine the need for IP and IP-like protections to incentive creation and sharing of data sets.102

- Collaborate with allies and partners to promote pro-innovation IP concepts, develop global disincentives for IP theft, and leverage international forums to increase representation for the United States and its allies and partners.103

Pushback: Coercive Economic Statecraft

Rebuilding America’s economic engine is essential to winning the competition, but without pushing back against Beijing’s economic malpractice, the United States will continue to fall behind. Each year, China inflicts economic damage on the United States that far exceeds the annual economic output of Virginia, or the annual sales of the entire global semiconductor market.104 The PRC has harnessed U.S. and allied technology, capital, and know-how to power its techno-economic ambitions and military modernization.105 America must join hands with its allies and partners, leveraging the tools of economic statecraft to fill gaps and push back aggressively against the threats the PRC poses to American economic and national security.

The Myth of a Level Playing Field: Examples of PRC Economic Malpractice

The PRC pursues distortionary economic policies on a scale that harms U.S. companies and workers and renders fair competition in international markets impossible. Examples include IP theft, forced technology transfer, cyber-enabled commercial espionage, market access restrictions, and industrial subsidies that far exceed what other governments provide and contravene China’s WTO commitments.106

- The PRC is the world’s leading perpetrator of IP theft, costing the United States up to $600 billion annually.107 For comparison, this exceeds Virginia’s total economic output ($591 billion in 2021).108

- The PRC is the largest origin economy for counterfeit and pirated goods, accounting for 92 percent of U.S. seizures in fiscal year 2019.109

- Between 1998 and 2018, Huawei received $75 billion in government financial support – subsidies designed to undercut rivals and drive out competition. China’s subsidy and export credit practices violate its WTO commitments. For comparison, Cisco has received $44.5 million in U.S. Government assistance since 2000.110

- The growing trade deficit with China cost the United States an estimated 3.7 million jobs between 2001 and 2018. The computer and electronic parts industry was hit the hardest, and three Congressional districts in Silicon Valley lost roughly 12 to 20 percent of total jobs in the districts.111

The PRC’s growing track record of economic malpractice means that a new approach is required. Attempts to convince the PRC to reign in its behaviors and compete on a “level playing field” have fallen flat.112 The last two decades have seen a more aggressive Beijing willing to break its international commitments, bend its corporate champions to the requirements of the state and military, and bully its trading partners.113 If left unchecked, the PRC’s pattern of behavior will inflict even more damage on higher value-added sectors and threaten national security in the United States and other advanced economies. To push back, America, in coordination with its allies and partners, must sharpen the tools of coercive economic statecraft and change incentives for Western companies and investors.

The United States and its allies must pursue collective economic self-defense. Beijing has made its choice clear114 – it seeks a one-way decoupling strategy to increase the world’s dependence on China while reducing China’s dependence on the world for critical technologies.115 For the United States and its allies, collective economic self-defense offers a more realistic and sustainable policy approach than ever-deepening entanglement and vulnerability to Beijing. This approach will put a price tag on the negative externalities that result from the PRC’s unfair and predatory behaviors, passing the costs on to the offender.

The United States should work together with allies and partners wherever possible to maximize leverage and eliminate gaps that the PRC can exploit.116 The United States will often have to lead the way, setting an example for allies and partners to follow. America’s large, diversified economy and low trade dependence on China (with goods exports to China equivalent to only 0.5 percent of U.S. GDP)117 means it can weather potential disruptions.

In many industries the United States remains the largest market118, and in many others it is by far the most lucrative and accessible one.119 The United States should be prepared to leverage access to its enormous and profitable market to redirect critical supply chains to domestic and ally- and partner-based production.

The objectives of this approach should be twofold:

- Diversification

The United States should form plurilateral frameworks with allies and partners to diversify supply chains, maximizing collective leverage vis-a-vis the PRC.120 Critics will frame such efforts as “decoupling” — an overwrought term that implies a sudden and total severing of economic ties. Rather, diversifying should proceed in a progressive and targeted fashion, starting with decisive steps to disentangle from the PRC where interdependence poses the greatest risks — especially dual-use technologies and critical infrastructure.

- Denial

As U.S. cash, technologies, and expertise flow into the PRC, American consumers, investors, and innovators end up reinforcing PRC malpractice at the expense of the home front, either knowingly or not. The United States and its allies should also seek to deny these flows to the PRC when they would contribute to China’s military development, fundamentally undermine the competitiveness of rule-of-law economies in high-tech sectors (such as semiconductors, aerospace, and biotechnology), or contribute to the PRC’s human rights abuses, including genocide and crimes against humanity in Xinjiang.121 As an example, U.S. venture capital firms, chip industry giants, and other investors participated in 58 investment deals with China’s semiconductor industry from 2017 to present, raising billions of dollars for PRC chip startups and helping them reach scale122 — accelerating China’s progress in a sector where it is important for America to remain ahead. In another example, U.S. and European companies and research institutions have helped Beijing build genomic surveillance programs for use in discriminatory law enforcement and political control against population in China and around the world.123 These activities should be banned.

The United States must update export controls for the age of emerging technology, strengthen existing inbound investment screening processes, and establish an effective outbound investment screening framework. Today, critical technologies built in U.S. laboratories – and billions of dollars of U.S. capital – flow into the PRC, accelerating China’s military modernization and technological progress in sectors where America must remain ahead.124 Stronger export control and investment screening measures are needed to ensure that the United States is not investing in its own decline.

Stronger export control and investment screening measures are needed to ensure that the United States is not investing in its own decline.

- Export Controls

Despite recent reforms, U.S. export controls are failing to stem the flow of advanced technology to the PRC.125 The Department of Commerce must identify and implement new controls on emerging technologies, pursuant to its obligations under Export Control Reform Act of 2018.126 Commerce should close the gaps in its current licensing policy to better enforce the controls introduced against PRC state champions, such as Huawei.127 Internationally, the United States should lead in the creation of a new multilateral export controls regime that addresses the contemporary challenges of national security, economic security, MCF128, and human rights issues, including the PRC genocide in Xinjiang.129 A PRC-focused approach can build off of the momentum and precedent created by the U.S. and allied coordination on the sweeping export controls on critical technological inputs in Russia’s industrial base.130

- Investment Screening

America must craft common-sense guardrails to curb the flow of know-how and investment dollars to China’s military and techno-economic engine and to incentivize investment flows into the United States and its allies instead. The Federal Government could take action by expanding the jurisdiction of CFIUS to review inbound investments in a wider set of technologies where adversary access would threaten U.S. national security131 and include oversight of more joint ventures and minority positions in investments.132 The United States must also establish an outbound investment screening process that can screen and block the flow of capital and know-how into its adversaries’ high-tech sectors (such as semiconductors, aerospace, and biotechnology) that undermine U.S. economic competitiveness and national security.

The United States and its allies should apply a “rebuttable presumption” – a standard innovatively applied policy innovation from the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) – to reduce exposure to the PRC in areas where U.S. private sector entanglement risks harming national security or advancing PRC strategic technology capabilities. For nearly a century, U.S. law has prohibited the import of products made with forced labor.133 The PRC’s lack of transparency complicates U.S. customs authorities’ ability to determine which imports from China meet that criterion. The logic of the UFLPA, which entered into force this year, is that the PRC’s extensive forced labor programs, restricted access to the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), and denial of routine supply chain reviews134 require the U.S. Government to shift the burden of proof to companies with XUAR-connected supply chains to show that they were not using forced labor in order to import products into the United States.135 This principle, known as “rebuttable presumption,” should be applied to other high-risk areas beyond forced labor. For example, a rebuttable presumption could address partnerships with entities linked to MCF and talent and technology transfer programs. This would not ban the interactions outright, but would place the burden of proof on the U.S. person wishing to conduct an activity to show that it is not harmful to national security. The rebuttable presumption would be much more powerful if applied alongside allies and partners.

1. Economic fundamentals can be framed in terms of key inputs or factors of production. These typically include land (i.e., natural resources), labor, and capital. Innovation, also known as total factor productivity, determines how productively these inputs are combined. SCSP assesses that the United States is beter of than China on land (as a net exporter of energy and agriculture; China is a net importer of both), labor (the U.S. workforce is highly productive and growing, while China’s is less productive and shrinking), and innovation. On capital, China is moving faster to accumulate physical capital (infrastructure and factories), while the United States has a strong lead in finance, which ofers advantages for productive investments. SCSP’s assessment was informed by Welcome to the Machine: A Comparative Assessment of the USA and China to 2035 Focusing on the Role of Technology in the Economy, Fathom Financial Consulting Limited (2022)

(SCSP-commissioned work product).

2. Welcome to the Machine: A Comparative Assessment of the USA and China to 2035 Focusing on the Role of Technology in the Economy, Fathom Financial Consulting Limited (2022) (SCSP-commissioned work product).

3. Beijing self-identifes as a Marxist-Leninist dictatorship and says that features of this system are essential to China’s success, including a “scientifc” assessment of world trends in which China is ascendent and western capitalism is in decline; a campaign-style approach to using people and resources to achieve national objectives; and long-term planning. Dan Tobin, How Xi Jinping’s New Era Should Have Ended U.S. Debate on Beijing’s Ambitions, Center for Strategic and International Studies (2020). For a thoroughly-researched, book-length treatment of the PRC’s grand strategy, see Rush Doshi, The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order, Oxford University Press (2021).

4. See Stephen Ezell, False Promises II: The Continuing Gap Between China’s WTO Commitments and Its Practices, Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (2021); Robert D. Atkinson, Innovation Drag: China’s Economic Impact on Developed Nations, Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (2020).

5. Klaus Schwab, The Global Competitiveness Report 2018, World Economic Forum at 33-34 (2018).

6. The U.S. has more than $6 trillion in outward FDI stocks, see Direct Investment by Country and Industry, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (2022). The second-largest source of FDI, the PRC, has a total stock of outward FDI of approximately $2 trillion, see U.S.-China Investment Ties: Overview, Congressional Research Service (2021).

7. Tom Orlick, et al., A Third of the Global GDP is Now Generated by Non-Democracies, Bloomberg (2022).

8. Richard Florida, Advanced Industries Still Rule the U.S. Economy—But It’s an Advantage That’s Slipping, Bloomberg (2015); FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Announces Supply Chain Disruptions Task Force to Address Short-Term Supply Chain Discontinuities, The White House (2021).

9. Mathew C. Klein, The American Dream: Bringing Factories Back to the U.S., Barron’s (2020); Robinson Meyer, The Bill That Could Truly, Actually Bring Back U.S. Manufacturing, The Atlantic (2021).

10. Between 1979 and 2019, the U.S. lost 6.7 million total manufacturing jobs. See Katelynn Harris, Forty Years of Falling Manufacturing Employment, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2020).

11. Remarks on a Modern American Industrial Strategy By NEC Director Brian Deese, The White House (2022).

12. SCSP has coined this term to refer to the approach proposed in this paper. It includes traditional elements of industrial strategy as commonly understood by economists, i.e. government intervention to stoke innovation and strengthen sectors considered essential for economic and national security, as well as other elements that are important to the competition with China, as laid out in the Preserve and Pushback sections of this chapter.

13. Mariana Mazzucato, et al., Industrial Policy’s Comeback, Boston Review (2021); Gregory Tassey, The Economic Rationales and Impacts of Technology-Based Economic Development Policies, Economic Policy Research Center at 1-8 (2018).

14. Charles Schultze, Industrial Policy: A Dissent, The Brookings Review (1983); Scot Lincicome & Huan Zhu, Questioning Industrial Policy: Why Government Manufacturing Plans Are Inefective and Unnecessary, Cato Institute (2021).

15. Marc Fasteau & Ian Fletcher, The Economic Foundations of Industrial Policy, Palladium (2020).

16. Markets often fail to account for the massive economic benefts that accrue from spending on R&D, infrastructure, and workforce training, and infrastructure. See, e.g., Timothy F. Bresnahan & Manuel Trajtenberg, General Purpose Technologies: “Engines of Growth?”, National Bureau of Economic Research at 18-21 (1992). On the benefts of government policies to boost R&D, see Welcome to the Machine: A Comparative Assessment of the USA and China to 2035 Focusing on the Role of Technology in the Economy, Fathom Financial Consulting Limited (2022) (SCSP-commissioned work product).

17. Martijn Rasser, et al., Reboot: Framework for a New American Industrial Policy, Center for a New American Security (2022); Walter M. Hudson, Geoeconomic Strategy and National Developmentalism, National Development (2022).

18. Remarks on a Modern American Industrial Strategy By NEC Director Brian Deese, The White House (2022).

19. Pub. L. 117-167, The CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 (2022).

20. Alexander Hamilton, Final Version of the Report on the Subject of Manufactures, U.S. Department of the Treasury (1791).

21. Maurice Baxter, Henry Clay and the American System, University Press of Kentucky at 49-54 (1995).

22. Michael Lind, Land of Promise: An Economic History of the United States, Harper at 152-153 (2012); Land-Grant College Act of 1862, Encyclopedia Britannica (last accessed 2022).

23. Arthur Herman, Freedom’s Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, Random House at 192-200 (2012); Charles A. Murray & Catherine Bly Cox, Apollo: The Race to the Moon, Simon & Schuster at 25 (1989).

24. Chiara Criscuolo, et al., Are Industrial Policy Instruments Efective?, OECD at 24-28 (2022).

25. In the context of national policy, this can occur as part of the technology action plans described in Chapter 1 of this report.

26. Philippe Aghion, et al., Industrial Policy and Competition, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics at 17-23 (2015).

27. The program set a “stretch goal” – rapid vaccine development and deployment – and used bar-seting criteria to select three promising vaccine technology platforms. Then, it baked competition into the program by selecting two companies per platform. See Moncef Slaoui & Mathew Hepburn, Developing Safe and Efective Covid Vaccines – Operation Warp Speed’s Strategy and Approach, New England Journal of Medicine (2020).

28. GAO-22-104611, National Strategy Needed to Guide Federal Eforts to Reduce Digital Divide, U.S. Government Accountability Ofice (2022); Robert D. Atkinson, How Applying ‘Buy America’ Provisions to IT Undermines Infrastructure Goals, Information Technology & Innovation Fund (2022).

29. John Hendel, Why Suspected Chinese Spy Gear Remains in America’s Telecom Networks, Politico (2022).

30. Nihal Krishan, FCC and NTIA Overhaul Spectrum Coordination Agreement, FedScoop (2022).

31. Accelerating 5G in the US, Center for Strategic and International Studies (2021).

32. Steven Levy, Huawei, 5G, and the Man Who Conquered the Noise, Wired (2020).

33. Patenting Activity Among 5G Technology Developers, U.S. Patent and Trademark Ofice at 1, 9 (2022).

34. ITI’s 5G Policy Principles and 5G Essentials for Global Policymakers, Information Technology Industry Council at 4 (2020).

35. Naima Hoque Essing, et al., The Next-Generation Radio Access Network: Open and Virtualized RANs Are the Future of Mobile Networks, Deloite (2020).

36. See Final Report, National Security Commission on Artifcial Intelligence at 191 (2021); see also Daniel Ho, et al., Building a National Research Resource: A Blueprint for a National Research Cloud, Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (2021).

37. Cyberspace Solarium Commission Report, U.S. Cyberspace Solarium Commission at 75 (2020).

38. Jason Perlow, A Summary of Census II: Open Source Software Application Libraries the World Depends On, The Linux Foundation (2022).

39. Eric Schmidt & Frank Long, Protect Open Source Software, Wall Street Journal (2022); Ashwin Ramaswami, Securing Open Source Software at the Source, Plaintext by Schmidt Futures (2021). While these assessments recommend centers for Open Source Software (OSS), the growth of open source hardware creates new opportunities and vulnerabilities that should be addressed as part of an Open Source Technology Center encompassing both hardware and software. See Ann Stefora Mutschler, Open Source Hardware Risks, Semiconductor Engineering (2020).

40. Jefrey Ding, The Rise and Fall of Great Technologies and Powers (2022).

41. Stephen Ezell, Assessing the State of Digital Skills in the U.S. Economy, Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (2021).

42. Remco Zwetsloot & Jack Corrigan, AI Faculty Shortages: Are U.S. Universities Meeting the Growing Demand for AI Skills?, Center for Security and Emerging Technology at 5-8 (2022); Stephanie Yang, Chip Makers Contend for Talent as Industry Faces Labor Shortage, The Wall Street Journal (2022).

43. Amanda Bergson-Shilcock, The New Landscape of Digital Literacy, National Skills Coalition at 4 (2020).

44. Final Report, National Security Commission on Artifcial Intelligence at 175 (2021).

45. Final Report, National Security Commission on Artifcial Intelligence at 368-372 (2021).

46. S. 4543, James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, § 1111, (2022).

47. In 2022, Purdue University unveiled the nation’s frst comprehensive Semiconductor Degrees Program for graduates and undergraduates, in partnership with various microelectronics frms. Purdue Launches Nation’s First Comprehensive Semiconductor Degrees Program, Purdue University (2022).

48. See e.g., Diana Gehlhaus & Luke Koslosky, Training Tomorrow’s AI Workforce: The Latent Potential of Community and Technical Colleges, Center for Security and Emerging Technology at 29-32 (2022).

49. Building Strong and Inclusive Economies through Apprenticeship, New America, Center on Education & Skills at New America (2019); Investments, Tax Credits, and Tuition Support, U.S. Department of Labor (last accessed 2022).

50. Entrepreneurship, New American Economy (last accessed 2022); John Letieri & Kenan Fikri, The Case for Economic Dynamism and Why it Maters for the American Worker, Economic Innovation Group (2022).

51. Graham Allison & Eric Schmidt, The U.S. Needs a Million Talents Program to Retain Technology Leadership, Foreign Policy (2022).

52. Global Talent Visa Program, Australian Government Department of Home Afairs (last accessed 2022); High Potential Individual (HPI) Visa, UK Government (last accessed 2022).

53. Military-Civil Fusion and the People’s Republic of China, U.S. Department of State (2020).

54. Alex Joske, The Chinese Communist Party’s Global Search for Technology and Talent, Australian Strategic Policy Institute (2020); Jordan Robertson, China’s Suspected IP Thieves Targeted by Twins’ Utah Startup, Bloomberg (2022).

55. Stuart Anderson, Biden Keeps Costly Trump Visa Policy Denying Chinese Grad Students, Forbes (2021).

56. See Proclamation Suspending Entry of Chinese Students and Researchers Connected to PRC “Military-Civil Fusion Strategy,”, NAFSA (2020). According to the State Department, only about one percent of PRC student visa applicants were afected. See Sha Hua, et al., Chinese Student Visas Tumble from Prepandemic Levels, Wall Street Journal (2022).

57. The University of California has developed a set of best practices and ofers training to others. See Elisa Smith, Research Security Symposium Focuses on Protecting America’s Intellectual Capital, University of California (2021).

58. Erik Brynjolfsson, The Turing Trap: The Promise & Peril of Human-Like Artifcial Intelligence, Daedalus (2022).

59. D. Joseph Stiglitz, Moving Beyond Market Fundamentalism to a More Balanced Economy, Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics at 345-351 (2009); Robert D. Atkinson, The Hamilton Index: Assessing National Performance in the Competition for Advanced Industries, Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (2022); Remarks on a Modern American Industrial Strategy By NEC Director Brian Deese, The White House (2022).

60. Keith Zhai, China Set to Create New State-Owned Rare-Earths Giant, Wall Street Journal (2021).

61. Valerie Bailey Grasso, Rare Earth Elements in National Defense: Background, Oversight Issues, and Options for Congress, Congressional Research Service at 4 (2013).

62. Russell Parman, An Elemental Issue, U.S. Army (2019).

63. Martin Placek, Share of the Global Lithium-Ion Batery Manufacturing Capacity in 2021 with a Forecast for 2025, by Country, Statista (2022); Govind Bhutada, Mapped: EV Batery Manufacturing Capacity, by Region, Visual Capitalist (2022); Global Gigafactory Pipeline Hits 300; the PRC Dominates but the West Gathers Pace, Benchmark Mineral Intelligence (2022).

64. U.S. Narrows Gap With China in Race to Dominate Batery Value Chain, Bloomberg NEF (2021).

65. Antonio Varas, et al., Strengthening the Global Semiconductor Value Chain in an Uncertain Era, Boston Consulting Group & Semiconductor Industry Association at 5 (2021).

66. Rare earths, bateries, and microelectronics each power emerging technologies with a variety of commercial and defense applications. The Department of Defense has identifed each of the above inputs as a critical vulnerability. Securing Defense-Critical Supply Chains: An Action Plan Developed in Response to President Biden’s Executive Order 14017, U.S. Department of Defense at 1-7 (2022).

67. Entrepreneurs and investors face steep barriers to entry in these sectors, including high capital expenditures, regulatory hurdles, supply chain complexity, and insuficient domestic industrial know-how. See Chris Power, et al., Rockets, Jets, and Chips: How to Modernize U.S. Manufacturing, Future (2022); John VerWey, No Permits, No Fabs: The Importance of Regulatory Reform for Semiconductor Manufacturing, Center for Security and Emerging Technology at 17-24 (2021); Yifei Huang, Software Is the Tech You Date, But Hardware Is the Tech You Marry, London Business School Private Equity & Venture Capital Blog (2022).

68. As of 2014, rare earth production supported about $300 billion in downstream economic activity. Ann Norman, et al., Critical Minerals: Rare Earths and the U.S. Economy, National Center for Policy Analysis at 3 (2014). The market for lithium-ion bateries alone is poised to reach $180 billion by 2030. Lithium-ion Batery Market Size Worth $182.53 Billion By 2030: Grand View Research, Inc, Bloomberg (2022). Microelectronics could become a trillion-dollar market by the end of the decade. Semiconductor shortages trimmed one percent of the U.S. GDP in 2021, but a supply shock due to a military contingency could be orders of magnitude worse. Ondrej Burkacky, et al., The Semiconductor Decade: A Trillion-Dollar IndustryStrategies to Lead in the Semiconductor World, McKinsey (2022); Jordan Fabian, Biden Aide Deese Says Semiconductor Shortage Cost 1% of U.S. GDP, Bloomberg (2022); Antonio Varas, et al., Strengthening the Global Semiconductor Value Chain in an Uncertain Era, Boston Consulting Group & Semiconductor Industry Association at 39-47 (2021).

69. Strategic Petroleum Reserve, U.S. Department of Energy (last accessed 2022).

70. Emily de La Bruyère & Nathan Picarsic, Elemental Strategy: Countering the Chinese Communist Party’s Eforts to Dominate the Rare Earth Industry, Foundation for the Defense of Democracies (2022).

71. Megan Lamberth, et al., The Tangled Web We Wove: Rebalancing America’s Supply Chains, Center for a New American Security at 11 (2022).

72. Minerals Security Partnership Media Note, U.S. Department of State (2022).

73. Michael Greenfeld, Is LFP Still the Cheaper Batery Chemistry After Record Lithium Price Surge?, S&P Global (2022).

74. Yuqing Chen, et al., A Review of Lithium-Ion Batery Safety Concerns: The Issues, Strategies, and Testing Standards, Journal of Energy Chemistry (2021).

75. Energy Report Part 1: Energy Storage, TechNext (2022) (SCSP-commissioned work product).

76. Ina Fried, Interview: Commerce Secretary on U.S. Chip Crisis, Axios (2021).

77. Pub. L. 117-167, The CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 (2022).

78. Antonio Varas, et al., Government Incentives and US Competitiveness in Semiconductor Manufacturing, Boston Consulting Group & Semiconductor Industry Association at 14-20 (2020).

79. Dylan Martin, TSMC’s 2025 Timeline for 2nm Chips Suggests Intel Gaining Steam, The Register (2022).

80. Will Hunt, Reshoring Chipmaking Capacity Requires High-Skilled Foreign Talent: Estimating the Labor Demand Generated by CHIPS Act Incentives, Center for Security and Emerging Technology (2022).

81. Stephanie Yang, Chip Makers Contend for Talent as Industry Faces Labor Shortage, The Wall Street Journal (2022); How the U.S. Can Reshore the Semiconductor Industry, Eightfold.AI (2022).

82. Margaret Harding McGill, Chip Makers Feel Labor Market Squeeze, Axios (2022).

83. Winning the Future: A Blueprint for Sustained U.S. Leadership in Semiconductor Technology, Semiconductor Industry Association at 13-14 (2019).

84. Will Hunt, Reshoring Chipmaking Capacity Requires High-Skilled Foreign Talent: Estimating the Labor Demand Generated by CHIPS Act Incentives, Center for Security and Emerging Technology at 11-12 (2022).

85. Dylan Patel, Why America Will Lose Semiconductors – Tangible Bi-Partisan Solutions for Solving a National Security Crisis, SemiAnalysis (2022).

86. Ryan Fedasiuk, et al., Silicon Twist: Managing the Chinese Military’s Access to AI Chips, Center for Security and Emerging Technology (2022).

87. Stu Woo & Yang Jie, The PRC Wants a Chip Machine From the Dutch. The U.S. Said No, The Wall Street Journal (2021).

88. Jenny Leonard, et al., China’s Chipmaking Power Grows Despite US Efort to Counter It, Bloomberg (2022).

89. Andre Barbe & Will Hunt, Preserving the Chokepoints: Reducing the Risks of Ofshoring Among U.S. Semiconductor Manufacturing Equipment Firms, Center for Security and Emerging Technology (2022); Stephen Nellis, The U.S. Weighs a Broader Crackdown on Chinese Chipmakers, The Information (2022).

90. Eswar Prasad, China’s Digital Currency Will Rise But Not Rule, Brookings (2020).

91. Rush Doshi, The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order, Oxford University Press at 247-250 (2021); PRC oficials are quoted as criticizing the “monopolistic position” of the U.S. dollar. See Jonathan Kirschner, The Great Wall of Money, Cornell University Press at 223 (2014).

92. Eswar Prasad, China’s Digital Currency Will Rise But Not Rule, Brookings (2020); Eswar Prasad, The Dollar Trap, Princeton University Press at 231-240 (2014).

93. Eswar Prasad, The Future of Money, Harvard University Press at 252-309 (2021).

94. Testimony of Samantha Hofman before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, An Assessment of the CCP’s Economic Ambitions, Plans, and Metrics of Success, Panel Four on “China’s Pursuit for Leadership in Digital Currency” (2021).

95. About the FedNow Service, The Federal Reserve (last accessed 2022).

96. These payment systems include the Federal Reserve, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), and the Clearing House Interbank Payment System (CHIPS). See Russell Wong, What is SWIFT, and Could Sanctions Impact the U.S. Dollar’s Dominance?, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond (2022).

97. What is a Central Bank Digital Currency?, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2021).

98. Testimony of Samantha Hofman before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, An Assessment of the CCP’s Economic Ambitions, Plans, and Metrics of Success, Panel Four on “China’s Pursuit for Leadership in Digital Currency” (2021).

99. EO 14067, Ensuring Responsible Development of Digital Assets (2022).

100. Final Report, National Security Commission on Artifcial Intelligence at 201-207 (2021); Kevin Madigan & Adam Mossof, Turning Gold to Lead: How Patent Eligibility Doctrine Is Undermining U.S. Leadership in Innovation, George Mason Law Review (2019).

101. Testimony of Judge Paul R. Mochel Before the Subcommitee on Intellectual Property, U.S. Senate Commitee on the Judiciary, The State of Patent Eligibility in America: Part I (2019).

102. Public Views on Artifcial Intelligence and Intellectual Property Policy, U.S. Patent and Trademark Ofice (2020).

103. In 2020, the United States successfully rallied allies and partners to support a Singaporean candidate, Daren Tang, as Director General for the World Intellectual Property Organization, trumping eforts by the PRC – the world’s leading infringer of IP rights – to install its own candidate. See Daniel F. Runde, Trump Administration Wins Big with WIPO Election, The Hill (2020).

104. The annual cost of IP theft, one vector of China’s economic malpractice, has been estimated between $225 to $600 billion. See Findings Of The Investigation Into China’s Acts, Policies, And Practices Related To Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, And Innovation Under Section 301 Of The Trade Act Of 1974, Ofice of the U.S. Trade Representative (2018). Counting other vectors – including subsidies, market distortions, market access restrictions, technology transfer, etc. – the number is signifcantly higher, but a single estimate does not exist. For comparison, Virginia’s annual economic output was approximately $492 billion in 2021. See Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the federal state of Virginia from 2000 to 2021, Statista (2022). Global semiconductor sales in 2020 totaled $440.4 billion. See Global Semiconductor Sales Increase 24% Year-to-Year in October; Annual Sales Projected to Increase 26% in 2021, Exceed $600 Billion in 2022, Semiconductor Industry Association (2021).

105. Military-Civil Fusion and the People’s Republic of China, U.S. Department of State (2020).

106. 2021 Special 301 Report, Ofice of the U.S. Trade Representative (2021). On industrial subsidies, see Gerard DiPippo et al., Red Ink: Estimating Chinese Industrial Policy Spending in Comparative Perspective, Center for Strategic and International Studies (2022).

107. Findings Of The Investigation Into China’s Acts, Policies, And Practices Related To Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, And Innovation Under Section 301 Of The Trade Act Of 1974, Ofice of the U.S. Trade Representative at Appendix C at 9 (2018).

108. Gross Domestic Product: All Industry Total in Virginia, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (2022).

109. 2021 Special 301 Report, Ofice of the U.S. Trade Representative at 16 (2021).

110. Chuin-Wei Yap, State Support Helped Fuel Huawei’s Global Rise, Wall Street Journal (2019). See also Stephen Ezell, False Promises II: The Continuing Gap Between China’s WTO Commitments and Its Practices, Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (2021).

111. Robert E. Scot & Zane Mokhiber, Growing China Trade Defcit Cost 3.7 million American Jobs Between 2001 and 2018, Economic Policy Institute at 19-20 (2020).

112. For example, in multilateral negotiations at the WTO since China’s accession in 2001, and the annual U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue, the PRC repeatedly commited to make market-oriented reforms but largely failed to do so. See 2021 Report to Congress on China’s WTO Compliance, Office of the U.S. Trade Representative at 7 (2022).

113. For more information on PRC economic coercion, see China’s Global Sharp Power Project, Hoover Institution; Peter Harrell, et al., China’s Use of Coercive Economic Measures, Center for a New American Security (2018); Adam Segal, Huawei, 5G, and Weaponized Interdependence in the Uses and Abuses of Weaponized Interdependence, Brookings Institution Press (2021); Thomas Cavanna, Coercion Unbound? China’s Belt adn Road Initiative in the Uses and Abuses of Weaponized Interdependence, Brookings Institution Press (2021).

114. For assessments of CCP intentions based on authoritative, primary source documents, see Rush Doshi, The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order (2021); Peter Matis, The Party Congress Test: A Minimum Standard for Analyzing Beijing’s Intentions, War on the Rocks (2019); Daniel Tobin, How Xi Jinping’s New Era Should Have Ended U.S. Debate on Beijing’s Ambitions, Center for Strategic and International Studies (2020).

115. On PRC policies to reduce reliance on advanced democracies while increasing their reliance on the PRC – recently dubbed “dual circulation” – see, for example, Testimony of Mat Potinger Before the United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission (2021); Rush Doshi, The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order, at 134-156 (2021). For an authoritative CCP policy document, see Translation: Outline of the People’s Republic of China 14th Five Year Plan, Center for Security and Emerging Technology (2021).

116. Aaron Friedberg, Getting China Wrong, Polity Press at 171-172 (2022).

117. U.S. GDP in 2020 was just over $20 trillion. GDP (Current US$) – United States, World Bank (2021). U.S. goods exports to China in 2020 were $123 billion – equivalent to half a percent of U.S. GDP. 2021 State Export Report, The U.S.-China Business Council (2021). The United States is the world’s largest exporter of services, but PRC market access restrictions means many U.S. services are blocked and thus exports are much lower than they would be if China were a normal economy.

118. Telecom Equipment Market Size is Projected to Grow at an 11.23% CAGR by 2025, Market Research Future (MRFR) (2021).

119. Rick Switzer, U.S. National Security Implications of Microelectronics Supply Chain Concentrations in Taiwan, South Korea and The People’s Republic of China, OCEA Occasional White Paper (2019).

120. “Plurilateral” groupings are agreements between two or more countries, but fewer than all members of an existing organization. See Delivering Plurilateral Trade Agreements within the World Trade Organization, UK Trade Policy Observatory at 5 (2021).

121. 2021 Report on International Religious Freedom: China – Xinjiang, U.S. Department of State (2022).

122. Kate O’Keefe, et al., U.S. Companies Aid China’s Bid for Chip Dominance Despite Security Concerns, Wall Street Journal (2022).

123. Sui-Lee Wee & Paul Mozur, China Uses DNA to Map Faces, with Help from the West, New York Times (2019); Emile Dirks & James Liebold, Genomic Surveillance, Australian Strategic Policy Institute (2020).

124. Kate O’Keefe, et al., U.S. Companies Aid China’s Bid for Chip Dominance Despite Security Concerns, Wall Street Journal (2022).

125. U.S. Export Controls and China, Congressional Research Service (2022).

126. Testimony of Nazak Nikakhtar before the Senate Select Commitee on Intelligence, Threats to U.S. National Security: Countering the PRC’s Economic and Technological Plan for Dominance (2022).

127. James Mulvenon, Seagate Technology and the Case of Missing Huawei FDPR Enforcement, Lawfare (2022).

128. Military-Civil Fusion and the People’s Republic of China, U.S. Department of State (2020).

129. Kevin Wolf & Emily S. Weinstein, COCOM’s Daughter?, WorldECR (2022).

130. Emily S. Weinstein, Making War More Dificult to Wage, Foreign Afairs (2022).

131. Emma Rafaelof, Unfnished Business: Export Control and Foreign Investment Reforms, U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (2021).

132. David Hanke, Hearing on U.S.-China Relations in 2021: Assessing Export Controls and Foreign Investment Review, U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (2021).

133. Cathleen D. Cimino-Isaacs, Section 307 and Imports Produced by Force Labor, Congressional Research Service (2022).

134. Haley Byrd Wilt, How the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act Became Law, Part 1, The Dispatch (2022).

135. See Uyghur Force Labor Protection Act, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (2022).